Vikings in Greenland

Jump to chapter

Published: 05/06/2020

Reading time: 11 minutes

Help! The Vikings are coming!

The world has become smaller and the process began long before we got the internet, global trading and round the world travel in less than the famous 80-days. No, the world already became smaller and more foreseeable, when Leif the Lucky went ashore on Labrador’s tree-clad coast around 1000 years ago.

What Leif the Lucky was looking for, was meat and water, but what he found were trees and people. With this journey and the subsequent attempts to settle in Vinland, the steady Viking intrusion across the North Atlantic to the north-western regions ended.

Vikings as explorers and commercial travelers

Pillaging, violent men from the High North, aggressive and with horns on their helmets – this is still our picture of these successful seafarers, the Vikings. We associate these words with romantic, heroic quests and follow their tracks in modern cruise ships.

But »Vikings« are the pirates who for the first time in 793 attacked the monastery at Lindisfarne, an island off the east coast of Northumbria. This attack is considered to be the start of the »Viking period«.

Previously, »to go Viking« meant to go raiding. These raiding trips were regular events and Vikings from Denmark, Sweden and Norway had divided the areas of Europe between them, where they stole valuable religious treasures in particular. Most of the gold was probably melted down, since archaeological digs have not produced any valuable treasure from churches.

The great explorers who later settled on the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland were not called Vikings, although some of them went to Ireland to steal slaves and wives.

The most remarkable thing about the Viking period, which stretched over hundreds of years, was not the plundering, but the voyages of discovery, the settlements, the spread of Christianity and the very successful trading connections.

Farmers as sea farers towards Greenland

One of the most important reasons for the wave of emigration in Norway in the 9th century was that power was concentrated among a few »Goder« (priests) and minor kings. Originally they ruled over the families in a small region, because they were the legislative authorities and especially also the religious leaders of the community.

The legislative and judicial powers in more complex cases gathered at the thing stead. This form of government had proved its worth over many centuries, but this changed when some of the Nordic »Goder« arrogated more power in a warlike manner. Some of the other »Goder« and freemen, who had thus lost their influence, decided therefore to immigrate, in particular to uninhabited lands like the Faroe Islands and Iceland. Scotland, the Orkney Islands and the Shetland Islands were also settled by the Vikings, but Picts and Celts had already lived here for thousands of years. Nevertheless, they managed to get along together, build new farms in the neighbourhood and in this way create favourably-situated bases for the Viking expeditions.

Only the Faroe Islands and Iceland were really actually colonised, when you disregard the Irish monks who had already lived there for come centuries. The monks were fond of the solitude of the islands in particular, because they were able to concentrate on their prayers.

The Viking ships sailing to Greenland

A prerequisite for these sea farers – whether they were pirates or explorers – was manoeuvrable vessels. The so-called Viking ships were developed in the 8th century. On one hand, they were war ships equipped with rudder and sail, and on the other hand, they were cargo ships that were deeper and had enough space for people and animals.

The light, fast ships were able to sail for long distances on open seas. They could easily moor at the coasts and just as easily leave again and they were ideal for expeditions.

In 1882 such a ship was found in Gokstad, where it had been placed as a burial gift. Isledningur, a lifelike copy of the ship from Gokstad, sailed in 2000 from Iceland over Greenland and Canada to Washington, D.C.

This memorable voyage followed Leif the Lucky’s legendary route. Captain Gunnar Marel captained the almost original Viking ship, which was fitted with a dragon head, but contrary to his ancestors, he had a compass.

The Vikings used a »sunstone« for navigation and were guided by the stars and the sun’s path. »Sunstone« is a mineral and its refraction was used to localise the sun on overcast days.

So although they were skilled seamen, their navigation was subject to the wiles of nature and it is therefore not surprising that several countries were discovered by coincidence.

Viking traces and documents

When we sail in the wake of the Vikings and visit the old settlements, we still find many ruins and much evidence from medieval times. Up to the present day archaeological excavations have been carried out and sometimes they have confirmed the accounts from the sagas. There are accounts of many voyages between Norway and Iceland due to the strong trading connections between the North Atlantic countries and the Scandinavian countries. Among others the Orkneyinga Saga and the Færeyinga Saga which are about battles for power and prestige, but not about the Viking voyages of conquest. Already in the 8th century the Vikings lived peacefully side by side with the Picts.

The Vikings prospered and thrived in Great Britain from the 10th to the 13thcenturies. The Orkney Islands was a duchy ruled by earls – the later »Earls« – who were afterwards installed by the Norwegian king. The most impressive evidence of the subsequent prolific building activity must be St Magnus Cathedral in Kirkwall, which was founded in 1137.

Today, it is mostly the town names and a few ruins on the islands that bear evidence of the Nordic past.

The settlers on the Faroe Islands and Iceland have left quite different traces. The present population is descended from the medieval settlers and both culture and language have developed from the old traditions. There are not many obvious traces like ruins on the Faroe Islands, although there is e.g. a royal farm and a bishopric which were built in the 12th century. Most of the walls of the old longhouses have gone, they are found only as integrated parts of newer houses or as building materials in other buildings, while others have been washed away by the sea.

After a prosperous period with independence, the new countries were again annexed by Norway. As a consequence of the political development, the island states came under Danish control and this would prove to be disastrous. The former so powerful and strong heroes from the middle ages described in the Icelandic Sagas had become, due to colonization and natural disasters, poor and oppressed farmers.

It is precisely the Icelandic Sagas that are important documentation for their lives and for the Icelanders’ exploration and trading voyages in the middle ages. Many farms have, for example, been excavated at the sites mentioned in the Sagas. Although the Sagas were written 300 years after the events they recount, there are bits of evidence that show they are not pure fiction.

On the trail of Erik the Red in Greenland

The true Vikings seem still to live on Iceland. Thanks to tourism, there is focus on this era of the country’s history.

There are museums that feature the subject, copies of long houses, halls for original Viking feasts and many other activities to add some spice to the country.

Ruins have been marked, excavated and exposed.

But there is a place, where the ruins have their own life – in a green landscape in the western part of the country, »Below the Snæfellsnes Glacier« there, where Erik the Red departed. From here he sailed south, searching for an area suitable for settling. He called the country he discovered »Greenland« – the green country – because he believed people would be attracted to a place with a nice name. This is written in »The Saga of the Greenlanders«.

Erik, who was outlawed, left Norway together with his father, when they were both sentenced to death for manslaughter and were later forced to leave Iceland for the same reason. He explored the west coast of Greenland, named fjords, mountains and glaciers and returned home after three years to find companions with whom he could undertake an actual settlement. »Knowledgeable men tell that in the same summer when Erik the Red settled in Greenland, twenty-five ships left Breiðarfjord and Borgarfjord headed for Greenland, but that only fourteen arrived. Some were forced to turn back and some were lost. This was in the fifteenth winter, before Christianity was adopted in Iceland.«

Erik the Reds’ Saga and the Vinland Sagas, which describe the voyages to Greenland and »Vinland« in Canada, belong together with the Saga of the Greenlanders.

Greenland and Vinland

In addition to the two explorers, Erik and his son Leif, Thorfinn Karlsefni and his wife Gudrid are at the centre of the accounts. It was they, who attempted to settle in Vinland. Later archaeological excavations have confirmed that there are Viking ruins at L’Anse aux Meadows. The attempts at settling here failed, because the Vikings ran into the so-called skraelings, as they named the local population. They were probably Inuit and Indian groups who were laying their claims to the area. Gudrid, who was given, in contrast to the male heroes, only a small memorial by the Icelanders, was probably the most travelled women of the medieval times, because later she travelled from Iceland to Rome.

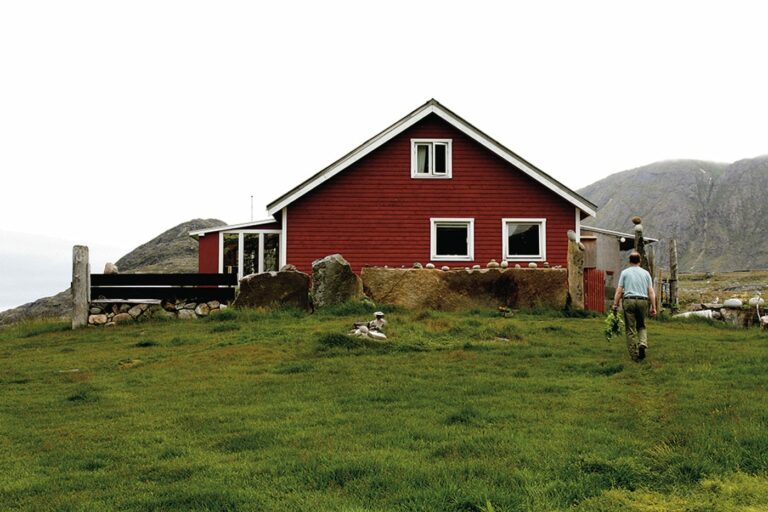

The ruins which, until today, are the most secretive are probably those at Hvalsey or Hvalsø in South Greenland. Here, not far from Qaqortoq, there is a fantastic group of ruins with a very well-preserved church. Opposite, there is the island of Hvalsø (Whale’s Island) which the place has been named after and which, according to how you look at it, resembles a whale.

Here, you rarely run into people, except when Edda Lyberth tells the cruise ship tourists about the Sagas, or Qaqortoq’s inhabitants are having a day out in the summer. The rest of the time there are only the sheep to enjoy the site.

If you walk around the ruins and look at the walls of the long houses with various side rooms and then sit down in the great hall, you get a feeling of what it was like 800 years ago. »On Sundays, the local farmers come here for services. Candles burned in niches in the church and sunlight shone through the windows, which were probably glazed. The flowers in the meadows swayed in the wind, the harvest would start in a few days so that the sheep that grazed in the fells would have enough to eat in the winter.«

The enigma of the Greenlandic Viking settlements still remains today; why were they abandoned and where did the people go? They lived in Greenland for about 450 years and the last written testament is about a marriage on September 14th, 1408 in Hvalsø Church.

Greenlandic Viking

In 1996, Elias Larsen from Sisimiut saw a magnificent, private sailing boat moor in the town’s harbour. On board was a group of American sailors.

– I drove them round and told them about the town.

To say thanks, they invited me to dinner on their boat that evening. Here, they told us they planned to build a copy of the Viking ship »Knarr« and repeat Leif Eriksson’s voyage from Greenland to North America

– They needed an extra man and when they asked if I wanted to go along, I of course said yes, tells Elias.

It was an exciting voyage which was both made into a film and published in book form: »A Viking Voyage« by W. Hodding Carter.

– It was a fantastic experience. I sailed with them along the coast of Greenland in 1997 and out into the Davis Strait, remembers Elias.

– We sailed in the dark and in all kinds of weather and we found a great respect for the old Vikings. From South Greenland (Bratthalid) we rowed like the Vikings have described in the sagas, all the way up to Disko Island (Bjørne Øen) and from here diagonally across towards Baffin Island (Helluland, the Land of Stone) because of the Gulf Stream up along Greenland’s west coast and the endless northern winds in the Davis Strait.

From there, it was the intention to sail to North Labrador (Markland), via South Labrador (Skovland) to Newfoundland (Vinland).

Unfortunately, the boat could not stand up to the tough weather and the others had to complete the voyage the following year without Elias Larsen, the Greenlandic Viking, who in the meantime had become director of what was then the Greenland Business Development Corporation, Sulisa.

Read more articles from Guide to Greenland

Guide to Greenland

You have come to Guide to Greenland's own page about all those who have contributed content and stories to our website. It is a varied group of good writers, journalists, employees, influencers, photographers and guests who have had good experiences in Greenland that they would like to share. Some stories come from our former magazine "Greenland Today". If you want to know more about the team behind Guide to Greenland, you can read the "about us" page. Thank you for your time and interest.

Go to author-

5.00(12)

Private Combined Boat & Kayaking tour by the Icefjord | Ilulissat

Tour startsIlulissatDuration3 hoursFrom 1 870 DKKSee more -

5.00(2)

Ukkusissaq Mountain Hike | Nuuk

Tour startsNuukDuration5 hoursFrom 2 575 DKKSee more -

Price for 4 people!

Hot Spring Uunartoq & Glacier landing by Helicopter | Qaqortoq | South Greenland

Tour startsQaqortoqDuration2.5 hoursFrom 7 725 DKKSee more -

5.00(1)

Sea Safari | Sisimiut | North Greenland

Tour startsSisimiutDuration2 hoursFrom 1 200 DKKSee more -

5.00(1)

4 hours Dogsledding tour| Ilulissat | Disko Bay

Tour startsIlulissatDuration4 hoursFrom 3 100 DKKSee more -

1 TO 6 PASSENGERS INCLUDED

Northern Lights Private Boat Tour | Nuuk

Tour startsNuukDuration3 hoursFrom 7 470 DKKSee more -

5.00(1)1 To 6 Passengers Included

The Calving Glacier Eqi | Private tour | Ilulissat | Disko Bay

Tour startsIlulissatDuration6 hoursFrom 13 920 DKKSee more -

5.00(17)Ideal For Cruise Guests

Private guided tour by car in the capital of Greenland | Nuuk

Tour startsNuukDuration1.5 hoursFrom 2 250 DKKSee more -

4.00(2)

Glacier Walk & Ice Cave Tour | East Greenland

Tour startsKulusuk TasiilaqDuration4.5 hoursFrom 2 950 DKKSee more -

Snowshoe to the top of Lille Malene | Nuuk

Tour startsNuukDuration5 hoursFrom 1 975 DKKSee more -

5.00(1)1 To 6 Passengers Included

The Calving Glacier Eqi & Paakitsoq | Ilulissat | Disko Bay

Tour startsIlulissatDuration8 hoursFrom 18 560 DKKSee more -

Sailing to Tiniteqilaaq and the Sermilik Icefjord | Tasiilaq | East Greenland

Tour startsTasiilaqDuration8 hoursFrom 2 000 DKKSee more -

Authentic experience!

Expedition on Dogsled | 2 Days | Ilulissat

Tour startsIlulissatDuration2 daysFrom 10 700 DKKSee more